Share This Article

The relationship between the Japanese and animals is little known in the West. Despite a history characterised by over a thousand years of bans on killing and eating certain species, Japan has become a major meat consumer since the Meiji era, particularly under Western influence. Whether they are leaders of animal rights organisations, researchers or simple activists, four Japanese talk to L’Amorce about the state of the movement for animal welfare in their country.

Interview by Joséphine G. and Tom Bry-Chevalier.

Presentation

Who are you, what do you do for animals and how long have you been involved in the animal rights movement in Japan?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: I am currently the president of Animal Welfare Corporate Partners Japan (AWCP) and have worked for The Humane League’s Japanese chapter, The Humane League Japan, from 2017 to the present. I’ve been involved in the animal welfare movement for around thirty years. I started working for the Alliance for Living Earth (ALIVE) and then with other international organisations to help solve animal welfare issues in Japan. About fifteen years ago, I returned to the university to specialise in animal welfare advocacy and policy, during which I studied the issue of farm animal welfare in detail.

Rei Nakama: I’m currently a PhD candidate at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT). I have been studying normative ethics and applied ethics, in particular animal ethics, for 4 years. I have been a vegetarian (flexitarian) for about 7 years, I donate to animal-related organisations and I sign petitions on the Internet. I have not yet been able to run an active campaign or become politically involved in any activity whatsoever.

Mineto Meguro: I’m the chairman of the political organisation Animalism Party and the founder and current director of the non-profit organisation Animal Liberator. Both organisations defend animal rights and are abolitionists. I became vegan in 2015 and started animal activism in 2016.

Amane Watahiki: I work for a company that supports businesses and producers who switch to producing and marketing eggs from non-caged hens. In my spare time, I volunteer to help animal rights groups in Japan. I’ve been involved in the animal rights movement since December 2021.

Historical background

What is the situation of the animal movement in Japan today?

Rei Nakama: I think that the general public has a poor understanding of this issue and that only a few interested people, researchers and activists, do what they can to help animals.

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: In Japan, awareness-raising activities carried out by pet protection groups have led to a significant reduction in the number of dogs and cats killed: whereas in 1990, around 145,000 dogs and 240,000 cats were slaughtered each year, by 2023 there would only be around 10,000. In addition to these activities, other initiatives are aimed at changing the law or improving the general public’s understanding of these issues. But on the other hand, certain problems concerning animals have not improved and are even getting worse, such as zoos, aquariums, animal breeding, animal experimentation, exotic animals and whaling. We continue to work, remaining positive and rejoicing in the small victories, but we know that there is still a lot of work to be done.

What is the history of animalist thought in Japan? What are the major influences (religious, historical, philosophical)?

Mineto Meguro: Current Japanese animalist thinking is inspired by Western thinking. But note that since 675, Japanese emperors have frequently issued decrees against eating meat and hunting, and certain shoguns[1] have issued similar orders since 1195. In the past, the emperors were followers of Buddhism, and the decrees they issued banning the consumption of meat were based on the precepts of non-killing. In 1687, the shogun Tsunayoshi Tokugawa had published the so-called “edicts of compassion for living beings”[2], based not on religious precepts but on his personal compassion for animals. These prohibitions were repeated until 1871, when the Meiji emperor and government lifted the ban on eating meat. The culture that had considered eating meat impure for over 1,000 years was then lost.

You mentioned the influence of Buddhism on the historical ban on eating certain meats in Japan. More generally, how have religions influenced Japanese perceptions of animals?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Shintoism, the native religion of Japan, invites people to honour nature and to consider animals as messengers of the gods (kami). This belief inspires deep respect for animals and their environment. For example, the fox (kitsune) is regarded as a sacred animal that acts as a messenger for the deity Inari, and as such is highly venerated and protected. This spiritual respect for animals extends to a broader cultural attitude that values the well-being of animals and emphasises living in harmony with nature.

From the 6th century onwards, the introduction of Buddhism in Japan reinforced respect for animals. Directives banning the consumption of meat greatly influenced Japanese opinion on animal welfare, encouraging the belief that it is morally reprehensible to harm animals.

However, although these fundamental spiritual and religious considerations are strongly embedded in the Japanese mind, I’m not sure that they appear explicitly in modern Japanese culture or that they permeate everyday life. For example, I don’t think consumers always take animal welfare into account when shopping.

In Japan, the livestock industry holds a ceremony called Chikukon-Sai. This ritual expresses deep gratitude and affection for the animals involved in breeding, dairy production and scientific experiments, by honouring and consoling their spirits. This ceremony has its origins in the Shinto belief that life resides in all things (Shinra Bansho)[3], but it is also sometimes practised in Buddhism, particularly where it has been mixed with Shinto practices.

Mineto Meguro: As I mentioned earlier, Buddhism, particularly under the impetus of successive emperors and shoguns, has created a culture that abhors the killing of animals. However, this taboo is not motivated by consideration for animal rights, but by a desire to avoid religious punishments, such as the punishment for violating the precept of non-violence[4] and the inability to reincarnate. In Shintoism, eating meat is also sometimes avoided, but this is said to be due to the influence of Buddhism. There may also be an obligation to respect certain animals considered sacred, but this has nothing to do with the animal rights movement.

What influence did the policy of opening up to the West during the Meiji era have on the consumption of animal products?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: During the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan underwent major changes as it opened up to Western countries and modernised, leading to greater exposure to Western eating habits. Western cuisine, which included more meat and dairy products, began to influence the Japanese diet. This change is part of a wider effort to adopt a more ‘civilised’ and modern lifestyle by encouraging Western dietary practices, which are perceived as beneficial to health and nutrition. By personally adopting a meat diet, the Meiji emperor helped spread this eating habit and contributed to the further westernisation of the whole of Japan[5].

Local challenges

What are the social and cultural meanings of animal products in Japan?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Animal products (chicken, pork, beef, milk, eggs and fish) are essential ingredients in the Japanese diet. Eggs in particular have a reputation for being stable and affordable, and are a source of protein for many people, making them indispensable on Japanese tables. Fish is also very popular, especially in dishes such as sushi and sashimi. All in all, animal products are deeply rooted in Japanese culinary traditions , cultural practices and social customs.

Rei Nakama: For city dwellers and the younger generation, I think the best explanation is that they consume animal products in their daily lives without giving them much social or cultural significance, without thinking about them in particular. I’m originally from the Okinawa region, known for its abundance of pork dishes. However, these days, I feel that few people in Okinawa eat pork with any awareness of the historical and cultural heritage in which this practice has been established.

What justifications do the Japanese use to rationalise their consumption of animal products?

Rei Nakama: With the exception of people I’ve made contact with in the context of research, none of my family, friends or partners are vegetarians. As a result, I’m often questioned and teased about my vegetarianism. I think that most people don’t think that eating animal products needs to be justified. In Japan today, it’s so ‘normal’ that vegetarians are considered eccentrics. Nevertheless, I would say that they justify themselves primarily with the following answers:

(1) Farmed animals are raised for consumption.

(2) Aren’t plants also forms of life?

(3) Humans are omnivores, so it’s natural.

It’s rare for anyone to discuss this topic seriously at the outset, but as the conversation progresses, the following objections emerge:

(4) What about carnivorous animals?

(5) What about industry? What about the people who work in it?

(6) A world where animal products are banned seems strange, like something out of science fiction.

(7) I understand that the issue of eating animal products is surprisingly complex. But it’s delicious, so I can’t stop.

(8) Since food is a matter of personal choice, and ultimately a matter of taste and preference, everyone is free to do what they want.

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: People believe that meat is necessary to maintain good health and a strong body. Due to growing health concerns, there is a tendency to prefer low-fat, high-protein meats such as chicken or fish. In addition, there are social influences at play; meat consumption can reflect social status and economic position, with high-quality meats and certain dishes often perceived as symbols of luxury and high social status.

Can you describe the current state of animal protection laws in Japan? How do they compare with international standards?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: There is a law on animal protection, administered by the Ministry of the Environment, which concerns farm animals. However, it contains no provisions for the protection of farm animals, and is therefore de facto useless and inadequate by international standards.

Amane : I can only refer to the ranking for Japan on the World Animal Protection website[6].

How does the animal protection movement in Japan compare with those in other East Asian countries?

Amane : My impression is that interest in animal protection is lower among the elites (people with degrees from reputable universities) than in other East Asian countries.

Do lobbies or public authorities strongly oppose the adoption of a plant-based diet?

Mineto Meguro: I’ve never heard of it. The animal cause is not yet considered a threat.

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: I don’t see any strong opposition to plant-based food, which seems to be seen as necessary for the future. I don’t claim that the majority of people share this point of view, but I have heard that companies recognise the need to reduce animal products. In my work on cage-free farming, I’m hearing more and more terms like ‘cage-free’ and ‘egg smart'[7], largely because of bird flu. During bird flu epidemics there is often a shortage of eggs, so efforts are made to stabilise supply by reducing egg consumption.

Are there any emblematic animal rights struggles in Japan (on issues such as whaling, for example)?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Yes, as you know, whaling, dolphin hunting (as in The Cove[8]), monkey shows, animal experimentation, the exploitation of exotic animals, and so on, are all part of the film.

Mineto Meguro: I don’t think that opposition to whaling or dolphin hunting comes from the animal rights movement. It was environmental activists who were at the heart of the anti-whaling movement, and few vegans seem to have been involved. As far as the fight against dolphin fishing is concerned, although it is an animal rights activity, it is not clear that it is part of a genuine animal rights movement.

How big is the pet industry in Japan and what efforts are being made to solve problems such as puppy mills and pet bars[9] ?

Rei Nakama: Although the law has been gradually amended in recent years, many problems remain, such as unscrupulous breeding and profit-driven pet shop management policies. When people consider adopting a pet, many think that pet shops are the only option.

What challenges does Japan face in improving the living conditions of farm animals, given its limited agricultural space and dependence on imported meat?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Limited space is not seen as a major problem. As far as hens are concerned, the problem of overproduction of eggs [excluding poultry crises] means that a reduction in the number of hens may not cause major problems availability . Despite this overproduction, there are still places where there are egg shortages, but this is a distribution problem. Dependence on meat imports, on the other hand, may slow down efforts to improve farm animal welfare at national level.

How is the animal movement structured in Japan?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: There is a cross-party initiative among politicians called Animal Giren, but I’m not sure it’s currently active. I don’t think there are any significant animal defence efforts from religious groups in Japan.

Successful citizens’ initiatives in Japan are virtually non-existent, not just on animal issues but in general. I think this is a major obstacle. In addition, animal protection organisations and the activists themselves are not very well trained. They often operate on a voluntary basis (partly because public support is limited), and there is a tendency to see exhausting, unpaid work as a virtue. I hope to see an evolution that will enable animal defenders to work strategically as professionals, and to achieve tangible results.

Nor is there a favourable environment for activists to flourish, as animal protection activities themselves have not yet fully developed . I think it’s very important for animal activists to develop their skills, to have decent salaries and a favourable working environment. I was lucky enough to have this opportunity when I was affiliated to the Humane League, and it’s thanks to this kind of professional support that you can progress in your work and find it fulfilling.

The best-known and largest animal rights organisation is the Animal Rights Center Japan (ARCJ), which deals with a wide range of animal issues. ARCJ’s director, Chihiro Okada, is a well-known and influential figure in this field. There used to be an equally influential organisation called ALIVE, which was active at government level, but it has fallen into disrepair since the death of its founder. PEACE and JAVA focus on animal testing issues. There are also many cat and dog rescue organisations. To my knowledge, there are only a handful of farm animal sanctuaries in Japan.

Mineto Meguro: In Japan, political organisations are different from political parties. A political party must meet specific criteria to be recognised as such. The Animalism Party therefore falls into the category of “other political organisations” (2913 organisations to date). There are 10 political parties in Japan, some of which have considerations for animals.

The political consideration of animals manifests itself from three distinct angles. Firstly, through the “Dobutsu Aigo” law (動物愛護)[10]For more information on this law: https://newsletter.nichibun.ac.jp/en/messages/1474/, a specifically Japanese approach to animal protection, which focuses primarily on companion animals and enjoys the support of the main political parties. Secondly, the issue of animal welfare in the broadest sense is also addressed by these same parties, which are working on various issues related to the subject. The third aspect, animal rights, remains largely ignored in the Japanese political landscape, with no party actively engaging with this more radical issue.

I’d like to stand in local elections next year and get involved in animal rights work.

JAVA, PEACE and Animal Liberator spring to mind. There are many shelters for dogs and cats. There are three shelters for farm animals that I know of. I don’t think there are any shelters for zoo animals.

Rei Nakama: I would also add: NPO Animal Rights Centre, PETA Japan, Eva, Association for Animal Environment and Welfare.

Are there any youth-led initiatives to reform animal protection in Japan?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: I think Effective Altruism Japan does an excellent job. There are also vegan clubs at universities, and many students are involved in protecting cats and dogs. However, most of them stop their activities when they start looking for a job or once they are employed because of company obligations or personal considerations.

Amane: Animal Ethics (AS) and its collaborators are launching the first Animal Ethics Congress this year or next! AS – Media for Animals, Ethics, and Philosophy is a youth organisation founded in 2019 that aims to explore and establish “a better relationship between animals and humans”. So far, readings and introductory events on animal ethics have been organised, as well as offering vegan menus to university co-ops and visits to animal farms and sanctuaries.

Strategy

What do you think are the main obstacles to the animal rights movement in Japan?

Rei Nakama: When it comes to animal ‘rights’, many people find the word ridiculous. They think that rights are a concept created by humans that only apply to humans. This is why people who defend animal rights are seen as bizarre, as loving animals too much, or as having radical ideas, and are therefore not taken seriously from the outset.

In Japan, people who talk about politics or get involved in social movements also tend to be looked down upon. I think the main obstacle is that the animal rights movement is not seen as a sensible movement, a reasonable movement, or a movement you should get involved in.

Mineto Meguro: The desire to eat animal products for their taste, the desire not to see or know, the difficulty of living as a vegan, the structure of political and financial interests, the concealment of information by the media, the lack of understanding of what constitutes rights, are all obstacles to the development and normalisation of the animal rights movement in Japan.

What have been the main advances and successes of the animal rights movement in Japan?

Mineto Meguro: There has been progress and success in protecting pets and wild animals. But I can’t remember any successes when it comes to animal rights, apart from selling books and publishing articles.

I think progress has been made by Animal Liberator with the creation of a website listing information on animal liberation and the setting up of the Animal Liberation Academy to identify and train animal activists in Japan.

Who are the influential figures and authors on animal issues in Japan today?

Rei Nakama: The academics include Tetsuji Iseda, Satoshi Kodama and Koji Asano. Taichi Inoue has translated many books on animal rights into Japanese.

What are the targets and preferred methods of action (companies, general public, public authorities) of animal rights activists?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: I think that the success of modes of action in Japan depends on public support. For example, activities that exert strong pressure to force change are often perceived as a ‘social nuisance’ in a Japanese society that is focused on harmony, which can alienate public opinion. Such efforts can be seen as isolated, eccentric and fanatical. Therefore, I think it’s essential to understand this, and to get various stakeholders to cooperate successfully in a peaceful manner, while gaining their support and aligning with public opinion and society.

Do you use the concept of speciesism and how is it translated into Japanese? Is it widely understood in Japanese society? What about the concept of sentience?

Mineto Meguro: The concept of discrimination based on species is used. It is translated very literally by the word [Shusabetu, 種差別]. Note that the Japanese word for “species” [Shu, 種] that makes up the term speciesism [Shusabetu, 種差別] also includes non-animal life, so an additional explanation is needed to talk about the fate inflicted on other animals. I would like to see a proper translation of this term into Japanese, which is not understood in Japanese society. On the other hand, I think there is a general understanding of the concept of sentience.

Amane : Concerning the term “speciesism”, there is a translation and I think the word “種差別” is sufficient. I have never heard the word [Shusabetu, 種差別] from the general public or major newspapers or TV programmes. It is only used or known by ethicists and animal defenders.

The term sentience (“有感性”) was suggested by the influential Japanese philosopher Tetsuji Iseda, yet he himself considers it a strange and artificial word. The term is only used by specialists in animal ethics. On the other hand, I notice that animal behaviourists and agro-economists use another translation, “感受性”, which is a fairly common word but does not reflect the real meaning of sentience. I would say that it rather means sensitivity , and has no direct implication on values or moral considerations.

Rei Nakama: I don’t think the term sentience is widely used in society either. However, I have the feeling that even those who are not convinced by animal ‘rights’ tend to embrace the concept of sentience.

How do Japanese animal protection organisations deal with the cultural emphasis on harmony and the avoidance of confrontation when advocating potentially controversial changes?

Amane : I think that this avoidance of confrontation is perhaps not so much due to the culture of harmony as to the law on defamation[11], the low level of funding for the Japanese animalist movement, and the tendency to avoid risks. This prevents them from campaigning against a particular company, a strategy that has proved effective in other countries.

In which direction would you like to see the Japanese animalist movement move?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: In Japan, animal welfare (for farm animals) is still in its infancy, and it is unfortunate that there is very little academic expertise and scientific research in this area. I would like to see a more in-depth exploration of these thoughts, my hypothesis being that the concept of animal welfare may not have existed in Japan, or that it was different from that in the West. Personally, I’d like to do more research in two areas: the history of the animal rights movement in Japan and continuing my academic research on the relationship with animals through positions on euthanasia in Japan, mainly with regard to pets. I’d be delighted to collaborate and present this work somewhere.

International collaboration and image

How has the whaling issue affected Japan’s international reputation for animal welfare, and what impact has this had on domestic efforts to defend animal rights?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Japan’s persistence in whaling and dolphin hunting is damaging the country’s reputation, but I don’t think it has much impact on the issue of farm animal welfare. What’s more, the same obstinacy can be found against every effort to defend animals and their welfare.

Rei Nakama: In my opinion, international criticism of whaling seems to have had a counter-productive effect in Japan. Instead of encouraging a rethink of the practice, it seems to have galvanised support for whaling, reinforcing the idea that it is an important tradition to be preserved in the face of outside pressure.

Amane : Although it’s shameful that whaling and dolphin hunting are still practised in our country, I don’t think the recent Greenpeace campaign is the best way to go about it. It triggered a distancing from the animal rights movement, which people saw as an expression of a cultural war being waged by the West against the East (or Japan). However, I have the impression that this view has weakened when it comes to the issue of farm animal welfare.

Do Japanese animal protection associations work with other foreign associations?

Maho Uehara-Cavalier: Personally, I’ve been working as a liaison between different international organisations for about 30 years. I’ve worked with organisations like ALIVE and collaborated with groups in the West and East Asia. Currently, organisations such as Open Wing Alliance/The Humane League and ARCJ work closely together (AWCP, my organisation, is currently keeping a certain distance, which is due to an earlier decision).

When international organisations seek to effectively support activities in Japan, it is essential that Japanese organisations provide them with a detailed explanation of Japanese culture, and that they understand this culture when they take action in our country. As I mentioned, if an action is perceived as a social nuisance, it takes a long time for it to cease to be seen as a harm, and for public confidence to be regained. It is therefore essential to listen carefully to the opinions of local activists and to act accordingly.

But I think campaigns abroad against Japanese companies or the government can be effective, because Japanese people, the government and companies are very concerned about how they are perceived globally.

Finally, to work effectively, it is important to translate everything into Japanese. If information is only available in French or English, there is a risk that it will be overlooked or ignored.

What could the French animal rights movement and readers of L’Amorce do to help the Japanese animal rights movement? What can we learn from the Japanese movement?

Mineto Meguro: I don’t think specific actions would work because Western Europe and Japan have different cultures, values, behaviours and social systems. Japan has its own way of doing things. For example, I think that the whaling issue has had some success thanks to Japanese organisations that have used their own strategies while receiving support from the West.

The other problem is funding. Animal rights groups in Japan are underfunded; the director of Animal Liberator, for example, works part-time while running her campaign[12]Here are the pages where you can support Animal Liberator and Animal Ethics..

Personally, I don’t think there are any lessons to be learned from the Japanese animal rights movement.

Rei Nakama : Although consideration for animal welfare is not yet widespread in Japan, Japanese society remains attentive to international trends, particularly those in developed nations. So, by outlining the current state of the animal protection movement in France and encouraging readers of L’Amorce to express their support for the animal cause in Japan, we could significantly increase the Japanese public’s interest in this movement. This approach could act as a catalyst for a wider awareness of animal rights in the country.

Amane : The Animal Protection Act, or rather the Dobutsu Aigo Act (動物愛護), is currently being revised (see Animal Protection Index). At the moment, Animal Rights Center, JAVA and PEACE are taking part in congressional meetings where the bill could be submitted and discussed as early as next year. These groups believe that it is very important to put pressure on Congress to amend the sections of the law concerning farm animals and animals used for experimentation. If the French animal rights movement and readers of L’Amorce can help to put pressure on the Japanese Congress, this could have a considerable impact. In particular, the Congress or the Japanese media are particularly sensitive to pressure from abroad. But we must also be careful not to trigger a backlash.

Illustration: Wild pig from the Bairei Gadan series, wood engraving. 1880s. By Kōno Bairei (1844-1895)

Chart and timeline: Tom Bry-Chevalier

Notes et références

| ↑1 | The shogunate was a political and military system that dominated Japan for several centuries, from 1192 to 1868. Under this system, a powerful military leader, the shogun, held effective power over the country, while the emperor retained a mainly ceremonial and symbolic role. The shogun directed the government, controlled the army and supervised the daimyos (feudal lords) who governed the various regions of Japan. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For more information on this subject, see the article by Tomohiro Kaibara (2022): “Les édits de compassion : animal, morale et politique dans le Japon du shogun Tsunayoshi (1687-1709)“. |

| ↑3 | According to our understanding, this is a very broad definition of life that includes sentients (e.g. animals) and non-sentients (e.g. trees), and even non-living beings (e.g. mountains) |

| ↑4 | In Buddhism, there is no formal system of sanctions or punishments for the violation of ethical precepts. Nevertheless, Buddhism teaches that violent actions can hinder spiritual progress and create negative karma, which will have unfavourable consequences in this or future lives. Moreover, in certain Buddhist communities, repeated and serious violations of the precepts can lead to a form of social ostracism or exclusion from certain community practices. |

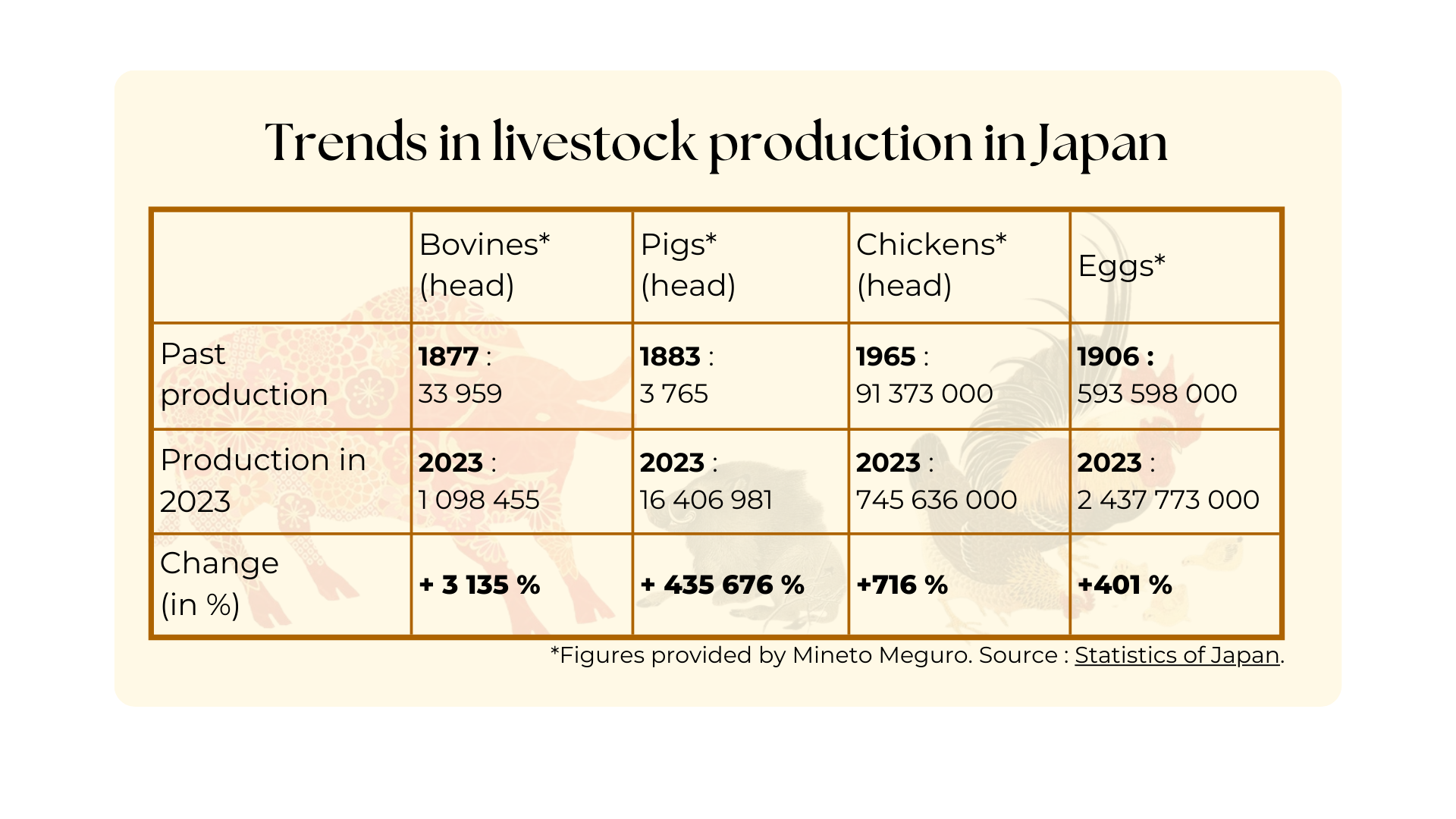

| ↑5 | See the table on changes in the number of animals slaughtered at the start of this article. |

| ↑6 | The Animal Protection Index, compiled by the NGO World Animal Protection, is a ranking of 50 countries around the world according to their legislation and political commitments in favour of animals. This ranking changes according to the political and regulatory developments in each country. |

| ↑7 | ”The “Egg-Smart Declaration” promises consumers to reduce or eliminate eggs within a certain timeframe. By halving the number of eggs used in a product, being creative and cooking without eggs, it is possible to improve animal welfare by moving away from mass production and consumption”. Source. |

| ↑8 | The Cove is a film that won the Oscar for Best Documentary Film in 2010. The film deals with the fishing of over 23,000 dolphins in a small bay in Taiji, Japan. |

| ↑9 | Pet bars are establishments where customers can interact with various animals while consuming drinks. They became increasingly popular in Japan in the 2000s, particularly among city dwellers who were unable to keep pets of their own. Most of the animals are cats, but there are also dogs, owls, hedgehogs, miniature pigs and even reptiles. |

| ↑10 | For more information on this law: https://newsletter.nichibun.ac.jp/en/messages/1474/ |

| ↑11 | Some background information on defamation law in Japan: – Unlike in many Western countries, the truthfulness of statements is not always a sufficient defence against a charge of defamation. – The Japanese media are often cautious in their investigations due to the strict nature of the law. – Penalties can include fines and even imprisonment (up to 3 years). |

| ↑12 | Here are the pages where you can support Animal Liberator and Animal Ethics. |